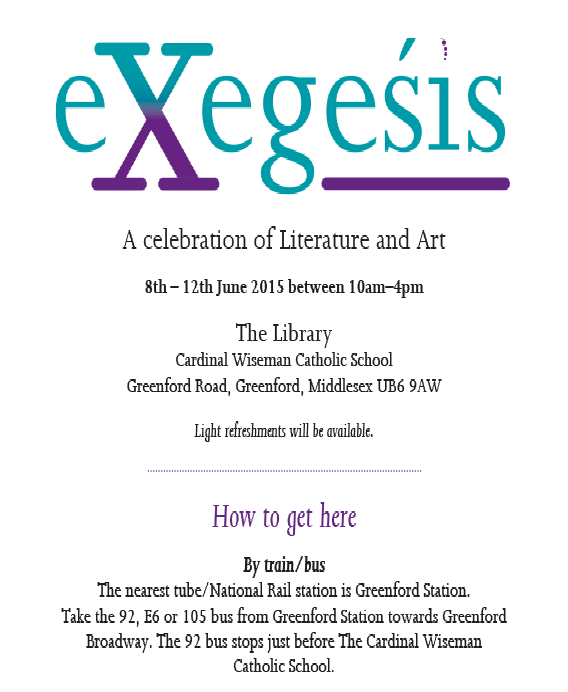

Exegesis 2015

RUN EXTENDED: Exegesis exhibition in the Library has been extended until Friday 19th June. On Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday we will be open from 10 am until 4pm , on Wednesday 10 am until 7pm. All welcome.

This is the list of extracts chosen by our first contributors, they are arranged in the order of the contributor’s surname. (Frank Cottrell Boyce chose two pieces and, as he is a good friend of the school, we were happy to let him do so.) The bibliographic details are for the copies we have in stock and we have taken the text from this copy.

We are hoping that you will choose one of these passages from which to create your artwork!

Please note that some books were chosen in their entirety and do not appear here.

They are the choices of:

- Aurelia Brambley – Antoine de Saint Exupery – Le Petit Prince

- Antony Gormley – Fyodor Dostoevsky – The Brothers Karamazov

- Baroness Jenny Jones – Nancy Mitford – Love in a Cold Climate

- Neal Zetter – Dr. Seuss – The Cat in the Hat

Click on the contributor' s name to read their passage:

Eliot, George (1991) Middlemarch London: Everyman [ISBN1857150112]

Finale: 889

Her finely-touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

From her email:

It is a tribute to the many quiet but important lives that go unsung: good for a catholic school!!

Brontë, Charlotte (1991) Jane Eyre London: Everyman [ISBN1857150104]

Chapter XII: 140-141

The ground was hard, the air was still, my road was lonely; I walked fast till I got warm, and then I walked slowly to enjoy and analyze the species of pleasure brooding for me in the hour and situation. It was three o’clock; the church bell tolled as I passed under the belfry; the charm of the hour lay in its approaching dimness, in the low-gliding and pale-beaming sun. I was a mile from Thornfield, in a lane noted for wild roses in summer, for nuts and blackberries in autumn, and even now possessing a few coral treasures in hips and haws; but whose best winter delight lay in its utter solitude and leafless repose. If a breath of air stirred, it made no sound here; for there was not a holly, not an evergreen to rustle, and the stripped hawthorn and hazel bushes were as still as the white, worn stones which causewayed the middle of the path. Far and wide, one each side, there were only fields, where no cattle now browsed; and the little brown birds which stirred occasionally in the hedge, looked like single russet leaves that had forgotten to drop.

This lane inclined up-hill all the way to Hay: having reached the middle, I sat down on a stile which led thence into a field. Gathering my mantle about me, and sheltering my hands in my muff, I did not feel the cold, though it froze keenly; as was attested by a sheet of ice covering the causeway, where a little brooklet, now congealed, had overflowed after a rapid thaw some days since. From my seat I could look down on Thornfield: the gray and battlemented hall was the principal object in the vale below me; its woods and dark rookery rose against the west. I lingered till the sun went down amongst the trees, and sank crimson and clear behind them. I then turned eastward.

On the hill-top above me sat the rising moon; pale yet as a cloud, but brightening momently: she looked over Hay, which, half lost in trees, sent up a blue smoke from its few chimneys; it was yet a mile distant, but in the absolute hush I could hear plainly its thin murmurs of life. My ear too felt the flow of currents; in what dales and depths I could not tell: but there were many hills beyond Hay, and doubtless many becks threading their passes. That evening calm betrayed alike the tinkle of the nearest streams, the sough of the most remote.

From her letter:

I cannot remember how old I was when I first read Jane Eyre. Young enough to experience for the first time the thrill of recognition, that things I felt were here represented, in wonderful language and that a place could be evoked so vividly as to include me in it. Just by reading, just by thinking of that passage thereafter I could be in that beautiful climbing lane on a January afternoon, the light fading, the moon rising, listening to the sound of streams, near and far.

Heller, Joseph (1994) Catch-22 London: Vintage [ISBN 9780099477310]

Chapter 9: 95-96

Major Major’s father was a sober God-fearing man whose idea of a good joke was to lie about his age. He was a long-limbed farmer, a God-fearing, freedom-loving, law-abiding rugged individualist who held that federal aid to anyone but farmers was creeping socialism. He advocated thrift and hard work and disapproved of loose women who turned him down. His speciality was alfalfa, and he made a good thing out of not growing any. The government paid him well for every bushel of alfalfa he did not grow. The more alfalfa he did not grow, the more money the government gave him and he spent every penny on new land to increase the amount of alfalfa he did not produce. Major Major’s father worked without rest at not growing alfalfa. On long winter evenings he remained indoors and did not mend harness, and he sprang out of bed at the crack of noon every day just to make certain that the chores would not be done. He invested in land wisely and soon was not growing more alfalfa than any other man in the country. Neighbors sought him out for advice on all subjects, for he had made much money and was therefore wise. ‘As ye sow, so shall ye reap,’ he counseled one and all, and everyone said, ‘Amen’.

From his reply:-

Happy to oblige for your Exegesis. My excerpt is enclosed. It comes from Catch 22, in my view the funniest book of the 20th century. But also one of the most important books because of how it captures the madness of the wars that ravaged the world in that period.

Brontë, Charlotte (1991) Jane Eyre London: Everyman [ISBN1857150104]

Chapter XXXVIII – Conclusion: 140

Reader, I married him.

From her email:

This was the first ‘grown-up” book I ever read, when I was about 10. I assumed then, romantically, that this was a straightforwardly happy ending. Now I know that last sentences of novels are always more complicated than that!

and …

This line isn’t actually the last line of the book, but is the first line of the last chapter which is called ‘Conclusion’, which is why I always remember it as the end of the book … it’s the conclusion of the book rather than its ending.

Luke 15: 11-32 The Story of the Prodigal Son

Jesus continued: “There was a man who had two sons. The younger one said to his father, ‘Father, give me my share of the estate.’ So he divided his property between them. “Not long after that, the younger son got together all he had, set off for a distant country and there squandered his wealth in wild living.

After he had spent everything, there was a severe famine in that whole country, and he began to be in need. So he went and hired himself out to a citizen of that country, who sent him to his fields to feed pigs. He longed to fill his stomach with the pods that the pigs were eating, but no one gave him anything. When he came to his senses, he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired servants have food to spare, and here I am starving to death! I will set out and go back to my father and say to him: Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son; make me like one of your hired servants.’ So he got up and went to his father.

But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion for him; he ran to his son, threw his arms around him and kissed him.

The son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’

But the father said to his servants, ‘Quick! Bring the best robe and put it on him. Put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. Bring the fattened calf and kill it. Let’s have a feast and celebrate. For this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.’ So they began to celebrate.

Meanwhile, the older son was in the field. When he came near the house, he heard music and dancing. So he called one of the servants and asked him what was going on. ‘Your brother has come,’ he replied, ‘and your father has killed the fattened calf because he has him back safe and sound.’

The older brother became angry and refused to go in. So his father went out and pleaded with him. But he answered his father, ‘Look! All these years I’ve been slaving for you and never disobeyed your orders. Yet you never gave me even a young goat so I could celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours who has squandered your property with prostitutes comes home, you kill the fattened calf for him!’

‘My son,’ the father said, ‘you are always with me, and everything I have is yours. But we had to celebrate and be glad, because this brother of yours was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.’”

Frank Cottrell Boyce

Vonnegut, Kurt (2000) Slaughterhouse 5 London: Virago [ISBN9780099800200]

Chapter 4: 53-54

… It was a move about American bombers in the Second World War and the gallant men who flew them. Seen backwards by Billy, the story went like this:

American planes, full of holes and wounded men and corpses took off backwards from an airfield in England. Over France, a few German fighter planes flew at the backwards, sucked bullets and shell fragments from some of the planes and crewmen. They did the same for wrecked American bombers on the ground, and those planes flew up backwards to join the formation.

The formation flew backwards over a German city that was in flames. The bombers opened their bomb bay doors, exerted a miraculous magnetism which shrunk the fires, gathered them into cylindrical steel containers, and lifted the containers into the bellies of the planes. The containers were stored neatly in racks. The Germans below had miraculous devices of their own, which were long steel tubes. They used them to suck more fragments from the crewmen and planes. But there were still a few wounded Americans though, and some of the bombers were in bad repair. Over France, though, German fighters came up again, made everything and everybody as good as new.

When the bombers got back to their base, the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating night and day, dismantling the cylinders, separating the dangerous contents into minerals. Touchingly, it was mainly women who did this work. The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground, to hide them cleverly, so they would never hurt anybody ever again.

The American fliers turned in their uniforms, became high school kids. And Hitler turned into a baby, …

From his letter:

… amazing bit from Slaughterhouse 5.

Billy Pilgrim survived the firebombing of Dresden in World War II but keeps having flashbacks to the night the whole city was burned to the ground. In this section, he wakes up in the middle of the night and watches a movie on TV …

Auster, Paul (1988r2004) The New York Trilogy London: Faber and Faber [ISBN9780571152230]

City of Glass [Book 1] Chapter 1: 3-7

It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not. Much later, when he was able to think about the things that happened to him, he would conclude that nothing was real except chance. But that was much later. In the beginning, there was simply the event and its consequences. Whether it might have turned out differently, or whether it was all predetermined with the first word that came from the stranger’s mouth, is not the question. The question is the story itself, and whether or not it means something is not for the story to tell.

As for Quinn, there is little that need detain us. Who he was, where he came from, and what he did are of no great importance. We know, for example, that he was thirty-five years old. We know that he had once been married, had once been a father, and that both his wife and son were now dead. We also know that he wrote books. To be precise, we know that he wrote mystery novels. These works were written under the name of William Wilson, and he produced them at the rate of about one a year, which brought in enough money for him to live modestly in a small New York apartment. Because he spent no more than five or six months on a novel, for the rest of the year he was free to do as he wished. He read many books, he looked at paintings, he went to the movies. In the summer he watched baseball on television, in the winter he went to the opera. More than anything else, however, what he like to do was walk. Nearly every day, rain or shine, hot or cold, he would leave his apartment to walk through the city – never really going anywhere, but simply going wherever his legs happened to take him.

New York was an inexhaustible space, a labyrinth of endless steps, and no matter how far he walked, no matter how well he came to know its neighbourhoods and streets, it always left him with the feeling of being lost. Lost, not only in the city, but within himself as well. Each time he took a walk, he felt as though he were leaving himself behind, and by giving himself up to the movement of the streets, by reducing himself to a seeing eye, he was able to escape the obligation to think, and this, more than anything else, brought him a measure of peace, a salutary emptiness within. The world was outside of him, around him, before him, and the speed with which it kept changing made it impossible for him to dwell on any one thing for very long. Motion was of the essence, the act of putting one foot in front of the other and allowing himself to follow the drift of his own body. By wandering aimlessly, all places became equal and it no longer mattered where he was. On his best walks, he was able to feel that he was nowhere. And this, finally, was all he ever asked of things: to be nowhere. New York was the nowhere he had built around himself, and he realized that he had no intention of ever leaving it again.

In the past, Quinn had been more ambitious. As a young man he had published several books of poetry, had written plays, critical essays, and had worked on a number of long translations. But quite abruptly, he had given up all that. A part of him had died, he told his friends, and he did not want it coming back to haunt him. It was then he had taken on the name of William Wilson. Quinn was no longer that part of him that could write books, and although in many ways Quinn continued to exist, he no longer existed for anyone but himself.

He had continued to write because it was the only thing he felt he could do. Mystery novels seemed a reasonable solution. He had little trouble inventing the intricate stories they required and he wrote well, often in spite of himself, as if without having to make an effort. Because he did not consider himself to be the author of what he wrote, he did not feel responsible for it and therefore was not compelled to defend it in his heart. William Wilson, after all, was an invention and even though he had been born within Quinn himself, he now led an independent life. Quinn treated him with deference, at times even admiration, but he never went so far as to believe that he and William Wilson were the same man. It was for this reason that he did not emerge from behind the mask of his pseudonym. He had an agent, but they had never met. Their contacts were confined to the mail, for which purpose Quinn had rented a numbered box at the post office. The same was true of the publisher, who paid all fees, monies, and royalties to Quinn through the agent. No book by William Wilson ever included an author’s photograph or biographical note. William Wilson was not listed in any writers’ directory, he did not give interviews, and all the letters he received were answered by his agent’s secretary. In the beginning, when his friends learned that he had given up writing, they would ask him how he was planning to live. He told them all the same thing: that he had inherited a trust fund from his wife. But the fact was that his wife had never had any money. And the fact was that he no longer had any friends.

It had been more that five years now. He did not think about his son very much anymore, and only recently he had removed the photograph of his wife from the wall. Every once in a while, he would suddenly feel what it had been like to hold the three-year-old boy in his arms – but that was not exactly thinking, nor was it even remembering. It was a physical sensation, an imprint of the past that had been left in his body, and for the most part it seemed as though things had begun to change for him. He no longer wished to be dead. At the same time, it cannot be said that he was glad to be alive. But at least he did not resent it. He was alive and the stubbornness of this fact had little by little begun to fascinate him – as if he had managed to outlive himself, as if he were somehow living a posthumous life. He did not sleep with the lamp on anymore, and for many months now he had not remembered any of his dreams.

It was night. Quinn lay in bed smoking a cigarette, listening to the rain beat against the window. He wondered when it would stop; and whether he would feel like taking a long walk or a short walk in the morning. An open copy of Marco Polo’s Travels lay face down on the pillow beside him. Since finishing the latest William Wilson novel two weeks earlier, he had been languishing. His private-eye narrator, Max Work, had solved an elaborate series of crimes, had suffered through a number of beatings and narrow escapes, and Quinn was feeling somewhat exhausted by his efforts. Over the years, Work had become very close to Quinn. Whereas William Wilson remained an abstract figure for him, Work had increasingly come to life. In the triad of selves that Quinn had become, Wilson served as a kind of ventriloquist. Quinn himself was the dummy, and Work was the animated voice that gave purpose to the enterprise. If Wilson was an illusion, he nevertheless justified the lives of the other two. If Wilson did not exist, he nevertheless was the bridge that allowed Quinn to pass from himself into work. And little by little, Work had become a presence in Quinn’s life, his interior brother, his comrade in solitude.

Quinn picked up the Marco Polo and started reading the first page again. ‘We will set down things seen as seen, things heard as heard, so that our book may be an accurate record, free from any sort of fabrication. And all who read this book or hear it may do so with full confidence because it contains nothing but the truth.’ Just as Quinn was beginning to ponder the meaning of the sentences, to turn their crisp assurances over in his mind, the telephone rang. Much later, when he was able to reconstruct the events of that night, he would remember looking at the clock, seeing that it was past twelve, and wondering why someone should be calling him at that hour. More than likely, he thought, it was bad news. He climbed out of bed, walked naked to the telephone, and picked up the receiver on the second ring.

‘Yes?’

There was a long pause on the other end, and for a moment Quinn thought the caller had hung up. Then, as if from a great distance there came the sound of a voice unlike any he had ever heard. It was at once mechanical and filled with feeling, hardly more than a whisper and yet perfectly audible, and so even in tone that he was unable to tell if it belonged to a man or a woman.

‘Hello?’ said the voice.

‘Who is this?’ asked Quinn.

‘Hello?’ said the voice again.

‘I’m listening,’ said Quinn. ‘Who is this?’

‘Is this Paul Auster?’ asked the voice. ‘I would like to speak to Mr Paul Auster.’

‘There’s no one here by that name.’

‘Paul Auster. Of the Auster Detective Agency.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Quinn. ‘You must have the wrong number.’

‘This is a matter of utmost urgency,’ said the voice.

‘There’s nothing I can do for you,’ said Quinn. ‘There is no Paul Auster here.’

‘You don’t understand,’ said the voice. ‘Time is running out.’

‘Then I suggest you dial again. This is not a detective agency.’

Quinn hung up the phone. He stood there on the cold floor, looking down at his feet, his knees, his limp penis. For a brief moment he regretted having been so abrupt with the caller. It might have been interesting, he thought, to have played along with him a little. Perhaps he could have found out something about the case – perhaps even have helped in some way. ‘I must learn to think more quickly on my feet,’ he said to himself.

From his email:

I’d like to choose the first pages of the New York Trilogy by Paul Auster. I found it very difficult to find books that grabbed me (in fact, I still do but now at least I know where to look). So when I was about 12 I drifted away from fiction and didn’t consider myself the kind of person who read books. I did try a couple of novels and enjoyed them, but I preferred avoiding books. I read a lot of cricket statistics and film magazines instead.

The people in my house who did read – a lot – were my sisters. My older sister was very good at suggesting books I might like. The couple of novels I managed to finish were the ones she’d recommended. I reached the 6th form still not bothered about fiction.

Then I was caught in a rainstorm in Hampstead High Street. It was after school and I was trying to get to the ice-cream shop (which tragically isn’t there any more). When the rain started hammering down the nearest door was Waterstones. I took cover. I wandered through the shop waiting for the rain to stop, but I wasn’t really browsing because I had no interest in the books. I didn’t pick up a single one. Then I saw a book on the tables called The New York Trilogy by Paul Auster. It caught my eye because that was one of the titles my sister had mentioned to me.

It was still raining so I picked up the book and started to read. I remember dripping onto the opening page. In the first couple of pages, the main character is woken up by a wrong number. The voice at the end of the phone asks to speak to Paul Auster. I turned back to check the author’s name which is, of course, Paul Auster. I’d never come across anything like that before. It was electrifying. I kept reading, bought the book and went home without any ice-cream.

That was the moment I became a reader again. From there, I gradually went through the rest of Paul Auster’s books, recommending them and sharing them with my friends as I went. After that I took on any book my sister suggested.

Without that first spark from the pages of New York Trilogy, I’d never have rediscovered reading, which means I would certainly never have been able to write a thing.

Jansson, Tove (2003) The Summer Book (Translated from the Swedish by Thomas Teal) London: Sort Of Books [ISBN9780954221713]

Chapter 1: 21-22

It was an early, very warm morning in July, and it had rained during the night. The bare granite steamed, the moss and crevices were drenched with moisture, and all the colours everywhere had deepened. Below the veranda, the vegetation in the morning shade was like a rainforest of lush, evil leaves and flowers, which she had to be careful not to break as she searched. She held one hand in front of her mouth and was constantly afraid of losing her balance.

“What are you doing?” asked little Sophia.

“Nothing,” her grandmother answered. “That is to say,” she added angrily, “I’m looking for my false teeth.”

The child came down from the veranda. “Where did you lose them?” she asked.

“Here,” said her grandmother. “I was standing right there and they fell somewhere in the peonies.” They looked together.

“Let me,” Sophia said. “You can hardly walk. Move over.”

She dived beneath the flowering roof of the garden and crept among green stalks and stems. It was pretty and mysterious down on the soft black earth. And there were the teeth, white and pink, a whole mouthful of old teeth.

“I’ve got them! the child cried, and stood up,”put them in.”

“But you can’t watch,” grandmother said. “That’s private.”

Sophia held the teeth behind her back.

“I want to watch,” she said.

So grandmother put the teeth in with a smacking noise. They went in very easily. It had really hardly been worth mentioning.

“When are you going to die?” the child asked.

And grandmother answered, “Soon. But that is not the least concern of yours.”

From his letter:

Like many another, I’ve long loved Tove Jansson’s Moomintroll books, but only quite recently did I come across her exquisite A Summer Book.

A Summer Book is set on a tiny island in the Baltic where a young girl, Sophia, has come to spend the summer with her grandmother (who lives there). I’m choosing the opening paragraphs of this book for a member of your school community to interpret, because they immediately grab our attentions (as good openings always must); they tell so much in so few words; because the scene is so superbly visualised; because they at once wittily establish the sort-of characters Sophia and her grandmother are and how their relationship may develop.

Multum in parvo! Such a simple and greatly promising passage. We the readers know there’s a treat in store, and turn the page …

Hopcke, Robert H. and Paul A. Schwartz (translators) (2006) “One of Saint Francis’s holiest of miracles, taming the fierce wolf of Gubbio” in Little Flowers of Saint Francis of Assisi Boston: New Seeds

p66-70

This tale rivals anything one might find in the Gospels for its endless breadth of possible interpretation. But whatever any of us might read into the figure of the wolf – innate human aggressiveness, selfishness, our hopeless propensity to violence, inability to love neighbour as oneself, mimetic rivalry – what is indisputable is what Francis reveals to the townspeople and to us: that compassion requires courage for it to become an agent of true transformation, and where courage and compassion are brought to bear, defensiveness, poverty and enmity can be turned into cooperation, abundance and familiarity.

During the time that Saint Francis lived in the town of Gubbio, there was in the town a large wolf, ferocious in behavior and terrible in appearance, who preyed not only upon the animals of the town but upon the townspeople as well. For this reason, they were greatly afraid of the wolf, and thus went about heavily armed at all times, lest they came upon it. Nevertheless, for all their precautions, any one who met the wolf alone was defenseless, such that after a time no one dared to venture outside the town at all.

Feeling great compassion for the people of Gubbio, Saint Francis decided to go out of the town and meet the wolf, which the townsfolk of course discouraged him from doing. But, making the sign of the cross and placing all his trust in God, he left the town with his companions who, after a time, seized by fear themselves, refused to go any further and left Saint Francis to meet the wolf on the road by himself.

Now many of the townspeople, wishing to see a miracle, followed at some distance behind Saint Francis. The wolf, seeing this great crowd, leapt forward toward Saint Francis, jaws wide open, but Saint Francis stepped toward him and made the sign of the Cross, calling out to him, “Come here, Brother Wolf. In Christ I command you to do no harm to me nor to anyone else.” What a wonder to recount! As soon as Saint Francis made this sign of the Cross, the ferocious wolf stopped in its tracks, closed its jaws, and became as gentle as a lamb, curling up at his feet.

Saint Francis spoke to it, saying, “Now, Brother Wolf, you have caused a lot of harm around here and have done some very evil things, hurting and killing God’s creatures without permission; and not only God’s animals, but you have even dared to kill human beings, who were made in the image of God. For this, by rights, you deserve to be hanged, like a thief or a murderer. Everyone curses you and says all manner of things against you, and the whole of this town is your enemy. But, Brother Wolf, I wish to make peace between you and your enemies, so that you no longer do them harm, so that they might forgive you all the evil you have done in the past, so that you no longer need to be hunted by men and dogs.” As he spoke, the wolf nodded his head in understanding of all Saint Francis was saying, his body, tail and ears completely attentive to everything Saint Francis did.

Further, Saint Francis said, “Brother Wolf, on my part, so that you keep the peace here in town, I promise you that I will see that, for the rest of your life, you are provided for by the townsfolk, so that you will never go hungry again, for I know that it is due to hunger that you have caused the harm you have caused. If I grant you this then, Brother Wolf, will you promise me now never again to harm any human being or animal? Is that a promise?” And once again the wolf nodded as a sign of his promise.

Saint Francis concluded then by saying, “Brother Wolf, I would like you to give me a pledge of your promise, so that I might have faith in it,” extending his hand to receive this pledge of faith from the wolf, who raised his right paw and placed it upon Saint Francis’s hand, giving him his solemn pledge.

“Brother Wolf, “said Saint Francis, “I command you, in the name of Christ Jesus, to trust me completely and to come with me now to seal this peace in the name of God.” Obediently the wolf went with him, following him as a little lamb would, to the great astonishment of the townspeople, who spread the news of this happening far and wide throughout the city such that everyone, man, woman, short, tall, young and old, all came to the town square to see the wolf with Saint Francis.

With the whole of the town before him, Saint Francis went up and began to preach to them, telling them, among other things, how for our sins God allows plagues and other evil things to occur, but that the fires of hell are far more dangerous and last an eternity for those who are damned – unlike the rage of a mere wolf who can only kill our bodies. “How much more than the mouth of a mere animal should we fear the raging mouth of hell itself? Change your lives, my dear friends, turn to God and renounce you own evil ways. God will deliver you from the wolf of your present life and from the fires of hell in the life to come.”

Finishing his sermon, Saint Francis then said, “Listen, my brothers and sisters: our brother Wolf here before you has given me his promise and a pledge of his faith, that he has made his peace with you all and will no longer do you any harm, for which you are to give him all that he needs. I stand here a guarantee that he will observe the peace he has pledged.”

The whole town answered by promising that they would indeed make sure the wolf was always well fed, and before them, Saint Francis turned to the wolf and said, “And you, Brother Wolf, do you promise to observe this covenant of peace and to do no harm to human beings, animals, or any living creature?”

The wolf knelt before him and, with gentle gestures of his body, tail, and ears, nodded his head giving sign as he could of his promise to keep this covenant.

Saint Francis then said, “Brother Wolf, I wish for you to give me once more a pledge of your promise, as you did earlier outside of town, here now before all the townspeople so that you will not betray your promise nor my guarantee of you to them.” So the wolf raised his right paw and placed it in Saint Francis’s hand, at which the townspeople marveled and rejoiced, as much out of devotion to Saint Francis as for the novelty of the miracle they had witnessed and the peaceful demeanor of the wolf. Raising their voices to heaven, they praised and blessed God for having sent them Saint Francis, who through his merits had delivered them from the mouth of this cruel beast.

For two more years the wolf lived among them in Gubbio and went about from door to door, as a friend to all, harming no one and without being harmed in any way himself, being given food to eat by one and all, without even so much as a dog barking at him, until, at the end to the two years, he died of old age. The people of Gubbio were much grieved by his passing, for they had grown used to his gentle presence in the town, which reminded them at all times of the virtue and sanctity of Saint Francis.

Praise be to Jesus Christ and to his poor servant Francis.

Amen.

From his letter:

I read this story of St Francis and the Wolf at a very difficult and depressed time in my life. The stories in this book act like the Gospel parables and can have hundreds of levels of interpretation. For me, at a time of great darkness, the idea of the wolf being tamed, accepted and fed, changed something in me and gave me hope.

It is easy to celebrate what is light and joyful in ourselves but sometimes very difficult to reconcile the darkness. In other versions of this story the townspeople ask Francis to get rid of the wolf. Francis however tells them that he has spoken to THEIR wolf and told him that they will feed him.

The good news of the Gospel is for the whole world, not just a small part.

I wanted to get rid of my depression, expel it, be finished with it. This story suggested to me that the good news of the Gospel is proclaimed to all of me. What is good and what feels dark and painful needs to be brought together into the healing light.

Pratchett, Terry (2005) A Hat full of Sky London: Corgi [ISBN9780552551441]

Chapter 10: The Late Bloomer pp257-258

… there was the Raddles’ privy. Miss Level had explained carefully to Mr and Mrs Raddle several times that it was too close to the well, and so the drinking water was full of tiny, tiny creatures that were making their children sick. They’d listened very carefully, every time they heard the lecture, and still they never moved the privy. But Mistress Weatherwax told them it was caused by Goblins who were attracted to the smell and by the time they left that cottage Mr Raddle and three of his friends were already digging a new well the other end of the garden.

‘It really is caused by tiny creatures, you know’, said Tiffany, who’d once handed over an egg to a travelling teacher so she could line up and look through his “ **Astounding Mikroscopical Device! A Zoo in Every Drop of Ditchwater!**” She’d almost collapsed next day from not drinking. Some of those creatures were hairy.

‘Is that so?’ said Mistress Weatherwax sarcastically.

‘Yes. It is. And Miss Level believes in telling them the truth!’

‘Good. She’s a fine honest woman,’ said Mistress Weatherwax. ‘But what I say is, you have to tell people a story they can understand. Right know I reckon you would have to change quite a lot in the world, and maybe bang Mr Raddles’ stupid fat head against the wall a few times, before he’d believe that you can be sickened by drinking tiny invisible beasts. And while you’re doing that, those kids of theirs will get sicker. But goblins, now, they make sense today. A story gets things done …

From his email:

It may seem strange, with the wealth of great literature to choose from, to opt for a passage from a children’s fantasy novel. I confess to already being a fan of Terry Pratchett before I read A Hat Full of Sky, but this little section stood out for me as a storyteller, and I made a note of it immediately after reading it.

One of the most important voices in the world of teaching is the American psychologist, Jerome Bruner. he has suggested that we understand the world through two, equally important, ways of thinking, which can be simply explained as scientific and narrative (or story). In this passage, Terry Pratchett uses his wonderful comic creation, Granny Weatherwax, to explore the difference between these two ways of seeing the world: Miss Level ( a school teacher) describes the world in scientific terms, while Mistress Weatherwax (the local witch) prefers the power of stories.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott (2006) The Great Gatsby London: Penguin [ISBN9780141023434]

Chapter 9: 183-184

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that's no matter--tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. . . And one fine morning -

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

From the letter dictated to his secretary:

…nominate the last paragraph of The Great Gatsby a fine piece of prose which was read at the funeral of his sister-in-law who had spent many years in the United States.

Joyce, James (1991) Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man London: Everyman [ISBN1857150090]

III: 133-142

-Remember only thy last things and thou shalt not sin for ever - words taken, my dear little brothers in Christ, from the book of Ecclesiastes, seventh chapter, fortieth verse. In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

Stephen sat in the front bench of the chapel. Father Arnall sat at a table to the left of the altar. He wore about his shoulders a heavy cloak; his pale face was drawn and his voice broken with rheum. The figure of his old master, so strangely re-arisen, brought back to Stephen's mind his life at Clongowes: the wide playgrounds, swarming with boys; the square ditch; the little cemetery off the main avenue of limes where he had dreamed of being buried; the firelight on the wall of the infirmary where he lay sick, the sorrowful face of Brother Michael. His soul, as these memories came back to him, became again a child's soul.

— We are assembled here today, my dear little brothers in Christ, for one brief moment far away from the busy bustle of the outer world to celebrate and to honour one of the greatest of saints, the apostle of the Indies, the patron saint also of your college, Saint Francis Xavier. Year after year, for much longer than any of you, my dear little boys, can remember or than I can remember, the boys of this college have met in this very chapel to make their annual retreat before the feast day of their patron saint. Time has gone on and brought with it its changes. Even in the last few years what changes can most of you not remember? Many of the boys who sat in those front benches a few years ago are perhaps now in distant lands, in the burning tropics, or immersed in professional duties or in seminaries, or voyaging over the vast expanse of the deep or, it may be, already called by the great God to another life and to the rendering up of their stewardship. And still as the years roll by, bringing with them changes for good and bad, the memory of the great saint is honoured by the boys of this college who make every year their annual retreat on the days preceding the feast day set apart by our Holy Mother the Church to transmit to all the ages the name and fame of one of the greatest sons of catholic Spain.

—Now what is the meaning of this word retreat and why is it allowed on all hands to be a most salutary practice for all who desire to lead before God and in the eyes of men a truly christian life? A retreat, my dear boys, signifies a withdrawal for awhile from the cares of our life, the cares of this workaday world, in order to examine the state of our conscience, to reflect on the mysteries of holy religion and to understand better why we are here in this world. During these few days I intend to put before you some thoughts concerning the four last things. They are, as you know from your catechism, death, judgement, hell, and heaven. We shall try to understand them fully during these few days so that we may derive from the understanding of them a lasting benefit to our souls. And remember, my dear boys, that we have been sent into this world for one thing and for one thing alone: to do God's holy will and to save our immortal souls. All else is worthless. One thing alone is needful, the salvation of one's soul. What doth it profit a man to gain the whole world if he suffer the loss of his immortal soul? Ah, my dear boys, believe me there is nothing in this wretched world that can make up for such a loss.

—I will ask you, therefore, my dear boys, to put away from your minds during these few days all worldly thoughts, whether of study or pleasure or ambition, and to give all your attention to the state of your souls. I need hardly remind you that during the days of the retreat all boys are expected to preserve a quiet and pious demeanour and to shun all loud unseemly pleasure. The elder boys, of course, will see that this custom is not infringed and I look especially to the prefects and officers of the sodality of Our Blessed Lady and of the sodality of the holy angels to set a good example to their fellow-students.

—Let us try, therefore, to make this retreat in honour of saint Francis with our whole heart and our whole mind. God's blessing will then be upon all your year's studies. But, above and beyond all, let this retreat be one to which you can look back in after years when maybe you are far from this college and among very different surroundings, to which you can look back with joy and thankfulness and give thanks to God for having granted you this occasion of laying the first foundation of a pious honourable zealous christian life. And if, as may so happen, there be at this moment in these benches any poor soul who has had the unutterable misfortune to lose God's holy grace and to fall into grievous sin, I fervently trust and pray that this retreat may be the turningpoint in the life of that soul. I pray to God through the merits of His zealous servant Francis Xavier, that such a soul may be led to sincere repentance and that the holy communion on saint Francis's day of this year may be a lasting covenant between God and that soul. For just and unjust, for saint and sinner alike, may this retreat be a memorable one.

—Help me, my dear little brothers in Christ. Help me by your pious attention, by your own devotion, by your outward demeanour. Banish from your minds all worldly thoughts and think only of the last things, death, judgement, hell, and heaven. He who remembers these things, says Ecclesiastes, shall not sin for ever. He who remembers the last things will act and think with them always before his eyes. He will live a good life and die a good death, believing and knowing that, if he has sacrificed much in this earthly life, it will be given to him a hundredfold and a thousandfold more in the life to come, in the kingdom without end - a blessing, my dear boys, which I wish you from my heart, one and all, in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen!

As he walked home with silent companions, a thick fog seemed to compass his mind. He waited in stupor of mind till it should lift and reveal what it had hidden. He ate his dinner with surly appetite and when the meal was over and the grease-strewn plates lay abandoned on the table, he rose and went to the window, clearing the thick scum from his mouth with his tongue and licking it from his lips. So he had sunk to the state of a beast that licks his chaps after meat. This was the end; and a faint glimmer of fear began to pierce the fog of his mind. He pressed his face against the pane of the window and gazed out into the darkening street. Forms passed this way and that through the dull light. And that was life. The letters of the name of Dublin lay heavily upon his mind, pushing one another surlily hither and thither with slow boorish insistence. His soul was fattening and congealing into a gross grease, plunging ever deeper in its dull fear into a sombre threatening dusk while the body that was his stood, listless and dishonoured, gazing out of darkened eyes, helpless, perturbed, and human for a bovine god to stare upon.

The next day brought death and judgement, stirring his soul slowly from its listless despair. The faint glimmer of fear became a terror of spirit as the hoarse voice of the preacher blew death into his soul. He suffered its agony. He felt the deathchill touch the extremities and creep onward towards the heart, the film of death veiling the eyes, the bright centres of the brain extinguished one by one like lamps, the last sweat oozing upon the skin, the powerlessness of the dying limbs, the speech thickening and wandering and failing, the heart throbbing faintly and more faintly, all but vanquished, the breath, the poor breath, the poor helpless human spirit, sobbing and sighing, gurgling and rattling in the throat. No help! No help! He, he himself, his body to which he had yielded was dying. Into the grave with it! Nail it down into a wooden box, the corpse. Carry it out of the house on the shoulders of hirelings. Thrust it out of men's sight into a long hole in the ground, into the grave, to rot, to feed the mass of its creeping worms and to be devoured by scuttling plump-bellied rats.

And while the friends were still standing in tears by the bedside the soul of the sinner was judged. At the last moment of consciousness the whole earthly life passed before the vision of the soul and, ere it had time to reflect, the body had died and the soul stood terrified before the judgementseat. God, who had long been merciful, would then be just. He had long been patient, pleading with the sinful soul, giving it time to repent, sparing it yet awhile. But that time had gone. Time was to sin and to enjoy, time was to scoff at God and at the warnings of His holy church, time was to defy His majesty, to disobey His commands, to hoodwink one's fellow men, to commit sin after sin and to hide one's corruption from the sight of men. But that time was over. Now it was God's turn: and He was not to be hoodwinked or deceived. Every sin would then come forth from its lurkingplace, the most rebellious against the divine will and the most degrading to our poor corrupt nature, the tiniest imperfection and the most heinous atrocity. What did it avail then to have been a great emperor, a great general, a marvellous inventor, the most learned of the learned? All were as one before the judgementseat of God. He would reward the good and punish the wicked. One single instant was enough for the trial of a man's soul. One single instant after the body's death, the soul had been weighed in the balance. The particular judgement was over and the soul had passed to the abode of bliss or to the prison of purgatory or had been hurled howling into hell.

Nor was that all. God's justice had still to be vindicated before men: after the particular there still remained the general judgement. The last day had come. Doomsday was at hand. The stars of heaven were falling upon the earth like the figs cast by the fig-tree which the wind has shaken. The sun, the great luminary of the universe, had become as sackcloth of hair. The moon was bloodred. The firmament was as a scroll rolled away. The archangel Michael, the prince of the heavenly host, appeared glorious and terrible against the sky. With one foot on the sea and one foot on the land he blew from the arch-angelical trumpet the brazen death of time. The three blasts of the angel filled all the universe. Time is, time was, but time shall be no more. At the last blast the souls of universal humanity throng towards the valley of Jehoshaphat, rich and poor, gentle and simple, wise and foolish, good and wicked. The soul of every human being that has ever existed, the souls of all those who shall yet be born, all the sons and daughters of Adam, all are assembled on that supreme day. And lo, the supreme judge is coming! No longer the lowly Lamb of God, no longer the meek Jesus of Nazareth, no longer the Man of Sorrows, no longer the Good Shepherd, He is seen now coming upon the clouds, in great power and majesty, attended by nine choirs of angels, angels and archangels, principalities, powers and virtues, thrones and dominations, cherubim and seraphim, God Omnipotent, God Everlasting. He speaks: and His voice is heard even at the farthest limits of space, even in the bottomless abyss. Supreme Judge, from His sentence there will be and can be no appeal. He calls the just to His side, bidding them enter into the kingdom, the eternity of bliss prepared for them. The unjust He casts from Him, crying in His offended majesty: depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire which was prepared for the devil and his angels. O, what agony then for the miserable sinners! Friend is torn apart from friend, children are torn from their parents, husbands from their wives. The poor sinner holds out his arms to those who were dear to him in this earthly world, to those whose simple piety perhaps he made a mock of, to those who counselled him and tried to lead him on the right path, to a kind brother, to a loving sister, to the mother and father who loved him so dearly. But it is too late: the just turn away from the wretched damned souls which now appear before the eyes of all in their hideous and evil character. O you hypocrites, O, you whited sepulchres, O you who present a smooth smiling face to the world while your soul within is a foul swamp of sin, how will it fare with you in that terrible day?

And this day will come, shall come, must come: the day of death and the day of judgement. It is appointed unto man to die and after death the judgement. Death is certain. The time and manner are uncertain, whether from long disease or from some unexpected accident; the Son of God cometh at an hour when you little expect Him. Be therefore ready every moment, seeing that you may die at any moment. Death is the end of us all. Death and judgement, brought into the world by the sin of our first parents, are the dark portals that close our earthly existence, the portals that open into the unknown and the unseen, portals through which every soul must pass, alone, unaided save by its good works, without friend or brother or parent or master to help it, alone and trembling. Let that thought be ever before our minds and then we cannot sin. Death, a cause of terror to the sinner, is a blessed moment for him who has walked in the right path, fulfilling the duties of his station in life, attending to his morning and evening prayers, approaching the holy sacrament frequently and performing good and merciful works. For the pious and believing catholic, for the just man, death is no cause of terror. Was it not Addison, the great English writer, who, when on his deathbed, sent for the wicked young earl of Warwick to let him see how a christian can meet his end? He it is and he alone, the pious and believing christian, who can say in his heart:

O grave, where is thy victory?

O death, where is thy sting?

From his letter:

The passage which has significant meaning for me is the Jesuit Priest’s sermon from A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce.

Shakespeare, William (2003) “Act 1, Scene II” from King Lear London: The Arden Shakespeare

pp179-180

Enter [EDMUND, the] Bastard [holding a letter].

EDMUND

Thou, Nature, art my goddess, to thy law

My services are bound. Wherefore should I

Stand in the plague of custom, and permit

The curiosity of nations to deprive me?

For that I am some twelve or fourteen moonshines

Lag of a brother? Why bastard? Wherefore base?

When my dimensions are as well compact,

My mind as generous and my shape as true

As honest madam’s issue? Why brand they us

With base? With baseness, bastardy? Base, base?

Who in the lusty stealth of nature take

More composition and fierce quality

Than doth within a dull stale tired bed

Go to the creating of a whole tribe of fops

Got ‘tween a sleep and wake. Well, then,

Legitimate Edgar, I must have your land.

Our father’s love is to the bastard Edmund

As to the legitimate. Fine word, ‘legitimate’!

Well, my legitimate, if this letter speed

And my invention thrive, Edmund the base

Shall top the legitimate. I grow, I prosper:

Now gods, stand up for bastards!

From her letter:

I have chosen this opening speech by Edmund from Shakespeare’s great Tragedy King Lear. Lear is a play of wisdom and foolishness, children and parents and young and old. In this extract we see Edmund’s sibling rivalry for his half-brother Edgar and how he demands to ‘top the legitimate’, rising from ‘base’ to become their father’s favourite and deceive him too.

Mostly, though, I chose this extract because it unlocked the language of Shakespeare for me when I was doing my A-Levels. From this point onward I understood Shakespeare’s language. I understood the power of plosives and have now shared this with countless students, the power of punctuation and rhetoric. I love the fact that the ending word of each line is just a small spiteful explosion. If you take the end word of each line you gain a small understanding of what he intends for the deception of his father and his brother. Time again, the best characters in Shakespeare are the evil ones. The audience aren’t meant to like them but we are made to be interested in them. Edmund is evil but I do enjoy his language in a play full of so many dark moments.

Mann, Thomas (1998) “Death in Venice” in Death in Venice and Other Stories (Translated by David Luke) London: Vintage

p204

… It was a pardonable error, indeed it was one that betokened as nothing else could the triumph of his moral will, that uninformed critics should mistake the great world of Maya, or the massive epic unfolding of Frederic’s life, for the product of solid strength and long stamina, whereas in fact they had been build up to their impressive size from layer upon layer of daily opuscula, from a hundred or a thousand separate inspirations; and if they were indeed so excellent , wholly and in every detail, it was only because their creator, showing that same constancy of will and tenacity of purpose as had once conquered his native Silesia, had held out for years under the pressure of one and the same task, and had devoted to actual composition only his best and worthiest hours.

Orwell, George (2008) 1984 London: Penguin [ISBN:9780141036144]

pp 144-145

Under the window somebody was singing. Winston peeped out, secure in the protection of the muslin curtain. The June sun was still high in the sky, and in the sun-filled court below, a monstrous woman, solid as a Norman pillar, with brawny red forearms and a sacking apron strapped about her middle, was stumping to and fro between a washtub and a clothes line, pegging out a series of square white things which Winston recognised as babies’ diapers. Whenever her mouth was not corked with clothes pegs she was singing in a powerful contralto:

It was only an ‘opeless fancy.

It passed like an Ipril dye,

But a look an’ a word an’ the dreams they stirred

They ‘ave stolen my ‘eart awye!

The tune had be haunting London for weeks past. It was one of the countless similar songs published for the benefit of the proles by a sub-section of the Music Department. The words of these songs were composed without any human intervention whatever on an instrument known as a versificator. But the woman sang so tunefully as to turn the dreadful rubbish into an almost pleasant sound. He could hear the woman singing and the scrape of her shoes on the flagstones, and the cries of children in the street, and somewhere in the far distance a faint roar of traffic, and yet the room seemed curiously silent, thanks to the absence of a telescreen.

From his letter:

I’m very pleased to be able to take part in this project – I hope the selection is useful to your students, as it meant a lot to me.

… and explanation:

Inn George Orwell’s ‘1984’ the repressed work-drone Winston Smith rents a shabby room in the Proles’ part of town where he can conduct forbidden trysts with Julia, the girl he has fallen in love with.

It’s the only place where he can truly be himself in this retro-futuristic state, where the government controls the lives of all, although they leave the working classes largely to themselves. Smith lives in constant fear.

There’s a moment when he looks out of the window of this room on a summer’s evening and sees a huge woman in the yard hanging out laundry and singing happily. She knows nothing of wars and politics, only of what’s she’s been told, and her lack of knowledge protects her from the terrors of life.

In that moment, the reader realises that Smith’s fate is to know too much, because once knowledge is imparted it can never be taken back, and he is therefore doomed to have an unhappy life no matter what he tries to do. He can never be like her. This scene haunted me as a student; the moment in life when you realise you now know too much of the world every to be naively happy again – it’s a loss of innocence that cannot be regained. Yet it’s also a moment of peace and happiness in the book, one of the very few.

If at that moment, looking down from his window, Smith could have traded his place for hers, would he have done so?

Eliot, George (1991) Middlemarch London: Everyman [ISBN1857150112]

Finale: 889

Her finely-touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

From her letter:

For me, Middlemarch is partly about the difficulties of not living up to one’s own expectations and the compromises we are obliged to make: Dorothea and Lydgate have such high hopes which are ultimately thwarted by society. In the end they do what they can and their lives are none the less heroic for that.

Quite often life gets in the way of our grand ambitions – having decided at the age of seven that I wanted to be a writer, I have certainly taken the scenic route to where I am now – and there is nothing to say that those who rest in unvisited tombs did not begin with their own quiet aspiration. There is no-one of public note in my family tree and yet my ancestors have all played their part in the history of this and other countries. The final words of Middlemarch are a timely reminder that they and others like them should not be forgotten.

Ishiguro, Kazuo (2005) The Remains of the Day London: Faber and Faber

pp188-189

… In any case, while it is all very well to talk of ‘turning points’ one can surely only recognize such moments in retrospect. Naturally, when one looks back to such instances today, they may indeed take the appearance of being crucial, precious moments in one’s life; but of course, at the time, this was not the impression one had. Rather, it was as though one had available a never-ending number of days, months, years in which to sort out the vagaries of one’s relationship with Miss Kenton; an infinite number of further opportunities in which to remedy the effect of this or that misunderstanding. There was surely nothing to indicate at the time that such evidently small incidents would render whole dreams forever irredeemable.

Lewis, C. S. (1971) The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Harmondsworth: Penguin

Chapter 1: Lucy Looks Into a Wardrobe: 12-16

Looking into the inside, she saw several coats hanging up – mostly long fur coats. There was nothing Lucy liked so much as the smell and feel of fur. She immediately stepped into the wardrobe and got in among the coats and rubbed her face against them, leaving the door open, of course, because she knew that it is very foolish to shut oneself into any wardrobe. Soon she went further in and found that there was a second row of coats hanging up behind the first one. It was almost quite dark in there and she kept her arms stretched out in front of her so as not to bump her face into the back of the wardrobe. She took a step further in – then two or three steps – always expecting to feel woodwork against the tips of her fingers. But she could not feel it.

‘This must be a simply enormous wardrobe!’ thought Lucy, going still further in and pushing the soft folds of the coats aside to make room for her. Then she noticed that there was something crunching under her feet. ‘I wonder is that more mothballs?’ she thought, stooping down to feel it with her hand. But instead of feeling the hard, smooth wood of the floor of the wardrobe, she felt something soft and powdery and extremely cold. ‘This is very queer,’ she said, and went on a step or two further.

Next moment she found that what was rubbing against her face and hands was no longer soft fur but something hard and rough and even prickly. ‘Why, it is just like branches of trees!’ exclaimed Lucy. And then she saw that there was a light ahead of her; not a few inches away where the back of the wardrobe ought to have been, but a long way off. Something cold and soft was falling on her. A moment later she found that she was standing in the middle of a wood at night-time with snow under her feet and snowflakes falling through the air.

Lucy felt a little frightened, but she felt very inquisitive and excited as well. She looked back over her shoulder and there, between the dark tree trunks, she could still see the open doorway of the wardrobe and even catch a glimpse of the empty room from which she had set out. (She had, of course, left the door open, for she knew that it is a very silly thing to shut oneself into a wardrobe.” It seemed to be still daylight there. ‘I can always get back if anything goes wrong,’ thought Lucy. She began to walk forward, crunch-crunch over the snow and through the wood towards the other light. In about ten minutes she reached it and found it was a lamp-post. As she stood looking at it, wondering why there was a lamp-post in the middle of a wood and wondering what to do next, she heard a pitter patter of feet coming towards her.

From her email:

I was a very impressionable child. I always loved stories that started with real life and then slipped into a parallel world or historical period. I have always believed that this is best type of fantasy and to this day I cannot discount that such ‘slippages’ do not happen. Throughout my life I have felt the back of many wardrobes. Just in case!

Of all the ways into Narnia, the Wardrobe was surely the best. Lewis’ description is so vivid that I can still smell the mothballs and feel the fur coats as they give way to the prickly branches and the crunch of snow underfoot.

As a reader I went through the Wardrobe with Lucy. Like her I relished that feeling of excitement tinged with fear, of being brave and keen to explore what was on the other side. Like me, Lucy was a good girl. Despite her curiosity, she left the Wardrobe door open so she would be able to get back. I would have done the same!

Dickens, Charles (1994) “A Christmas Carol” in The Christmas Books London: Penguin [ISBN 9780140620993]

pp26-28

Stave II The First of the Three Spirits – Familiar Scenes

'Good Heaven!' said Scrooge, clasping his hands together, as he looked about him. 'I was bred in this place. I was a boy here!'

The Spirit gazed upon him mildly. Its gentle touch, though it had been light and instantaneous, appeared still present to the old man's sense of feeling. He was conscious of a thousand odours floating in the air, each one connected with a thousand thoughts, and hopes, and joys, and cares long, long forgotten!

'Your lip is trembling,' said the Ghost. 'And what is that upon your cheek?'

Scrooge muttered, with an unusual catching in his voice, that it was a pimple; and begged the Ghost to lead him where he would.

'You recollect the way?' inquired the Spirit.

'Remember it!' cried Scrooge with fervour; 'I could walk it blindfold.'

'Strange to have forgotten it for so many years!' observed the Ghost. 'Let us go on.'

They walked along the road, Scrooge recognising every gate, and post, and tree; until a little market-town appeared in the distance, with its bridge, its church, and winding river. Some shaggy ponies now were seen trotting towards them with boys upon their backs, who called to other boys in country gigs and carts, driven by farmers. All these boys were in great spirits, and shouted to each other, until the broad fields were so full of merry music, that the crisp air laughed to hear it!

'These are but shadows of the things that have been,' said the Ghost. 'They have no consciousness of us.'

The jocund travellers came on; and as they came, Scrooge knew and named them every one. Why was he rejoiced beyond all bounds to see them! Why did his cold eye glisten, and his heart leap up as they went past! Why was he filled with gladness when he heard them give each other Merry Christmas, as they parted at cross-roads and by-ways for their several homes! What was merry Christmas to Scrooge? Out upon merry Christmas! What good had it ever done to him?

'The school is not quite deserted,' said the Ghost. 'A solitary child, neglected by his friends, is left there still.'

Scrooge said he knew it. And he sobbed.

They left the high-road, by a well-remembered lane, and soon approached a mansion of dull red brick, with a little weather-cock surmounted cupola on the roof, and a bell hanging in it. It was a large house, but one of broken fortunes; for the spacious offices were little used, their walls were damp and mossy, their windows broken, and their gates decayed. Fowls clucked and strutted in the stables; and the coach-houses and sheds were overrun with grass. Nor was it more retentive of its ancient state within; for, entering the dreary hall, and glancing through the open doors of many rooms, they found them poorly furnished, cold, and vast. There was an earthy savour in the air, a chilly bareness in the place, which associated itself somehow with too much getting up by candle light, and not too much to eat.

They went, the Ghost and Scrooge, across the hall, to a door at the back of the house. It opened before them, and disclosed a long, bare, melancholy room, made barer still by lines of plain deal forms and desks. At one of these a lonely boy was reading near a feeble fire; and Scrooge sat down upon a form, and wept to see his poor forgotten self as he had used to be.

Not a latent echo in the house, not a squeak and scuffle from the mice behind the panelling, not a drip from the half-thawed waterspout in the dull yard behind, not a sigh among the leafless boughs of one despondent poplar, not the idle swinging of an empty storehouse door, no, not a clicking in the fire, but fell upon the heart of Scrooge with softening influence, and gave a freer passage to his tears.

The Spirit touched him on the arm, and pointed to his younger self, intent upon his reading. Suddenly a man in foreign garments, wonderfully real and distinct to look at, stood outside the window, with an axe stuck in his belt, and leading by the bridle an ass laden with wood.

'Why, it's Ali Baba!' Scrooge exclaimed in ecstasy. 'It's dear old honest Ali Baba! Yes, yes, I know! One Christmas-time, when yonder solitary child was left here all alone, he did come, for the first time, just like that. Poor boy! And Valentine,' said Scrooge, 'and his wild brother, Orson; there they go! And what's his name, who was put down in his drawers, asleep, at the gate of Damascus; don't you see him! And the Sultan's Groom turned upside down by the Genii; there he is upon his head! Serve him right! I'm glad of it. What business had he to be married to the Princess?'

To hear Scrooge expending all the earnestness of his nature on such subjects, in a most extraordinary voice between laughing and crying; and to see his heightened and excited face; would have been a surprise to his business friends in the City, indeed.

'There's the Parrot!' cried Scrooge. 'Green body and yellow tail, with a thing like a lettuce growing out of the top of his head; there he is! Poor Robin Crusoe, he called him, when he came home again after sailing round the island. "Poor Robin Crusoe, where have you been, Robin Crusoe?" The man thought he was dreaming, but he wasn't. It was the Parrot, you know. There goes Friday, running for his life to the little creek! Halloa! Hoop! Halloo!'

Then, with a rapidity of transition very foreign to his usual character, he said, in pity for his former self, 'Poor boy!' and cried again.

'I wish,' Scrooge muttered, putting his hand in his pocket, and looking about him, after drying his eyes with his cuff; 'but it's too late now.'

'What is the matter?' asked the Spirit.

'Nothing,' said Scrooge. 'Nothing. There was a boy singing a Christmas carol at my door last night. I should like to have given him something: that's all.'

From her letter:

Miss Lumley would like to offer … - the passage when Scrooge is transported back into his boyhood by the Ghost of Christmas Past.

In it the reader sees how a lonely little boy, abandoned by people but immersed in his books, can turn into a sour twisted old man.

“I wish,” Scrooge muttered … “ but it’s too late now.”

The first glimpse of how regret can haunt you forever.

Hosseini, Khaled (2011) The Kite Runner London: Bloomsbury

p340

Behind us, kids are scampering and a melee of screaming kite runners was chasing the loose kite drifting high above the trees. I blinked and the smile was gone. But it had been there. I had seen it.

“Do you want me to run that kite for you?”

His Adam’s apple rose and fell as he swallowed. The wind lifted his hair. I thought I saw him nod.

“For you a thousand times over” I heard myself say.

Then I turned and ran.

It was only a smile , nothing more. It didn’t make everything all right. It didn’t make anything all right. Only a smile . A tiny thing. A leaf in the woods, shaking in the wake of a startled birds flight.

But I’ll take it. With open arms. Because when spring comes it melts the snow one flake at a time and maybe I just witnessed the first flake melting.

Austen, Jane (1992) Persuasion London: Everyman [ISBN1857150724]

Chapter XI: 230-235

‘…I will not allow it to be more man's nature than woman's to be inconstant and forget those they do love, or have loved. I believe the reverse. I believe in a true analogy between our bodily frames and our mental; and that as our bodies are the strongest, so are our feelings; capable of bearing most rough usage, and riding out the heaviest weather.'

'Your feelings may be the strongest,' replied Anne, 'but the same spirit of analogy will authorise me to assert that ours are the most tender. Man is more robust than woman, but he is not longer-lived; which exactly explains my view of the nature of their attachments. Nay, it would be too hard upon you, if it were otherwise. You have difficulties, and privations, and dangers enough to struggle with. You are always labouring and toiling, exposed to every risk and hardship. Your home, country, friends, all quitted. Neither time, nor health, nor life, to be called your own. It would be hard, indeed' (with a faltering voice), 'if woman's feelings were to be added to all this.'

'We shall never agree upon this question,' - Captain Harville was beginning to say, when a slight noise called their attention to Captain Wentworth's hitherto perfectly quiet division of the room. It was nothing more than that his pen had fallen down; but Anne was startled at finding him nearer than she had supposed, and half inclined to suspect that the pen had only fallen because he had been occupied by them, striving to catch sounds, which yet she did not think he could have caught.

'Have you finished your letter?' said Captain Harville.

'Not quite, a few lines more. I shall have done in five minutes.'

'There is no hurry on my side. I am only ready whenever you are. I am in very good anchorage here,' (smiling at Anne,) 'well supplied, and want for nothing. No hurry for a signal at all. Well, Miss Elliot,' (lowering his voice,) 'as I was saying we shall never agree, I suppose, upon this point. No man and woman, would, probably. But let me observe that all histories are against you - all stories, prose and verse. If I had such a memory as Benwick, I could bring you fifty quotations in a moment on my side the argument, and I do not think I ever opened a book in my life which had not something to say upon woman's inconstancy. Songs and proverbs, all talk of woman's fickleness. But perhaps you will say, these were all written by men.'

'Perhaps I shall. - Yes, yes, if you please, no reference to examples in books. Men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story. Education has been theirs in so much higher a degree; the pen has been in their hands. I will not allow books to prove anything.'

'But how shall we prove anything?'

'We never shall. We never can expect to prove anything upon such a point. It is a difference of opinion which does not admit of proof. We each begin, probably, with a little bias towards our own sex; and upon that bias build every circumstance in favour of it which has occurred within our own circle; many of which circumstances (perhaps those very cases which strike us the most) may be precisely such as cannot be brought forward without betraying a confidence, or in some respect saying what should not be said.'

'Ah!' cried Captain Harville, in a tone of strong feeling, 'if I could but make you comprehend what a man suffers when he takes a last look at his wife and children, and watches the boat that he has sent them off in, as long as it is in sight, and then turns away and says, 'God knows whether we ever meet again!' And then, if I could convey to you the glow of his soul when he does see them again; when, coming back after a twelvemonth's absence, perhaps, and obliged to put into another port, he calculates how soon it be possible to get them there, pretending to deceive himself, and saying, 'They cannot be here till such a day,' but all the while hoping for them twelve hours sooner, and seeing them arrive at last, as if Heaven had given them wings, by many hours sooner still! If I could explain to you all this, and all that a man can bear and do, and glories to do, for the sake of these treasures of his existence! I speak, you know, only of such men as have hearts!' pressing his own with emotion.

'Oh!' cried Anne eagerly, 'I hope I do justice to all that is felt by you, and by those who resemble you. God forbid that I should undervalue the warm and faithful feelings of any of my fellow-creatures! I should deserve utter contempt if I dared to suppose that true attachment and constancy were known only by woman. No, I believe you capable of everything great and good in your married lives. I believe you equal to every important exertion, and to every domestic forbearance, so long as - if I may be allowed the expression - so long as you have an object. I mean while the woman you love lives, and lives for you. All the privilege I claim for my own sex (it is not a very enviable one; you need not covet it), is that of loving longest, when existence or when hope is gone.'

She could not immediately have uttered another sentence; her heart was too full, her breath too much oppressed.

'You are a good soul,' cried Captain Harville, putting his hand on her arm, quite affectionately. 'There is no quarrelling with you. And when I think of Benwick, my tongue is tied.'

Their attention was called towards the others. Mrs Croft was taking leave.

'Here, Frederick, you and I part company, I believe,' said she. 'I am going home, and you have an engagement with your friend. To-night we may have the pleasure of all meeting again at your party,' (turning to Anne.) 'We had your sister's card yesterday, and I understood Frederick had a card too, though I did not see it; and you are disengaged, Frederick, are you not, as well as ourselves?'

Captain Wentworth was folding up a letter in great haste, and either could not or would not answer fully.

'Yes,' said he, 'very true; here we separate, but Harville and I shall soon be after you; that is, Harville, if you are ready, I am in half a minute. I know you will not be sorry to be off. I shall be at your service in half a minute.'

Mrs Croft left them, and Captain Wentworth, having sealed his letter with great rapidity, was indeed ready, and had even a hurried, agitated air, which shewed impatience to be gone. Anne knew not how to understand it. She had the kindest 'Good morning, God bless you!' from Captain Harville, but from him not a word, nor a look! He had passed out of the room without a look!

She had only time, however, to move closer to the table where he had been writing, when footsteps were heard returning; the door opened, it was himself. He begged their pardon, but he had forgotten his gloves, and instantly crossing the room to the writing table, and standing with his back towards Mrs Musgrove, he drew out a letter from under the scattered paper, placed it before Anne with eyes of glowing entreaty fixed on her for a moment, and hastily collecting his gloves, was again out of the room, almost before Mrs Musgrove was aware of his being in it - the work of an instant!